Today I’m sharing with you the powerful story someone sent to me a couple of weeks ago. The writer shares very openly and honestly about the blackness she experienced after making aliyah.

Today I’m sharing with you the powerful story someone sent to me a couple of weeks ago. The writer shares very openly and honestly about the blackness she experienced after making aliyah.

She says she used to think that things like this happened to people with dysfunctional childhoods – that’s how I used to think as well. I thought my children were guaranteed to never go through difficulties of this magnitude by raising them in a home with two loving parents filled with warmth, time, love and acceptance and appreciation for each one as he is. However, God has His plan for us and the potential to grow through hard times is always part of every person’s story.

Thank you Anonymous (she isn’t anonymous to me) for your courage in sharing your story to help others. I’ve changed some identifying details to protect her privacy.

**************************************

My Battle with Post Aliyah Depression

Who could have asked for more a perfect childhood and adolescence? I was blessed with loving parents, educational achievement, exemplary conduct, friends, as well as a strong belief in Hashem and Torah. My family was always there for me, I never had a need unmet. I worked diligently in high school and was accepted into my first-choice college. Thereafter, I graduated with high academic honors, had a wonderful experience in Torah seminary, and began an exciting career in political advocacy.

Soon thereafter, I met my soul-mate. Hashem gave us three beautiful children, a strong marriage, financial stability, health, a supportive Jewish community – my life was fulfilled. Then, without any warning, my husband was bit by the “aliyah bug,” and things were never the same again in in our household. We had just bought a second car and our first home, and we had had our second child when I was informed that, in order to fulfill our destiny, we must move halfway across the world to Israel.

Initially, I fought it. I was so happy in our Jewish community, the kids were doing well socially and academically, my husband had a great job, and—perhaps most significantly—we had a huge student loan debt that we could never foresee paying off on an Israeli salary and a house to sell in a market that had recently collapsed. My husband was not deterred by these obstacles. However, I was at least able to convince him that—although, yes, miracles happen in Eretz Yisrael—we cannot rely on that. He reluctantly agreed that we needed to sell our home first and pay off our debt before we could make aliyah.

My husband found a higher-paying job, and we started chipping away at the loans and the mortgage. After five years, and at a considerable loss, we were finally able to find a buyer for our house. Then, we found out about the possibility of receiving grant money from Nefesh B’Nefesh (NBN) upon making aliyah. If we were willing to move to the north of Israel, we could potentially get enough financial support from NBN to make aliyah a reality. The crux of the NBN Go North program was that participants were obligated to remain in north of the country for three years. After completing our pilot trip and some further research, we felt that northern Israel would likely match our needs and desires well. We loved the natural beauty, the weather, the topography, the slower pace of life, and the general culture of the Galilee and Golan. We also knew that my husband would be much more likely to find employment in the north in his profession and that the lower cost of living in this part of the country would allow us to hopefully buy a home there one day.

Despite personal reservations of mine about leaving all of our family, friends, culture, language, and everything familiar behind, I hopped aboard the aliyah train. I realized that my husband would never be content to remain the U.S., and I knew that living in Eretz HaKodesh would enable us to more fully follow the will of G-d and bring mitzvah observance to a whole new level. What I did not know was just how difficult making aliyah would be, especially to a part of the country which is somewhat isolated with few “Anglo-Saxons,” and therefore limited resources for English-speakers.

On arrival to our new home in a city in the upper Galilee, I discovered that everything was a struggle. We had no family in Israel and, at the time, we did not have any friends living in that part of the country and, therefore, no support system. We had not been able to afford a lift (shipment), so the initial stages of aliyah were about: sleeping on thin cots on the floor; managing without a refrigerator, washing machine and dryer; having no source of heat in the apartment; and managing without a car in one of the rainiest, coldest winters in Israel’s history. We had to leave the oven running with its door open 24 hours a day with its accompanying danger to our young kids in the home just to keep from freezing. Before we had any handle on Hebrew, we muddled our way through banking, using the post office, going grocery shopping, and paying bills. Making do without a car, I found myself frequently pushing a stroller in the rain for the thirty-minute walk to my daughter’s daycare only to walk drenched another half-hour to ulpan (intensive Hebrew language classes). The daily journey was reversed in the afternoon.

Shopping was a major obstacle in our area. I remember my husband once had to go to four stores to find cheap-quality adhesive tape. I did not know what food was kosher enough for us and what to avoid, at which restaurants it was okay to eat, or which fruits and vegetables had ma’aser (tithes) taken. Unlike the place we had come from in the U.S. where we felt welcomed and wanted, our new home had no real sense of community and I felt very alone. For the first time in our lives, we were surrounded by Jews, but each person seemed part of their own social group, and synagogues were a place to daven (pray), not make friends. Most people considered Shabbat a time to spend with their (Israeli) family and not to invite over guests, especially not those that could not even speak the language. The community center was great for after-school activities but not for meeting new people.

Because I could not speak Hebrew, I was no longer able to go to shiurim (Torah lectures) or cultural events, or even feel a part of society. I knew that I needed to learn Hebrew to thrive, so I diligently made the trek to and from ulpan daily, did all the homework assignments, and tried my best, but somehow that was not enough. I got sick in the middle, took a leave of absence and rejoined another group a few months later. After completing Ulpan Aleph (beginners’ level) twice, I spoke Hebrew at about the level of a two- year-old. Somehow, I was able to master college-level physics, biology, chemistry, and calculus but Hebrew was something my brain could not grasp.

Compared with my pre-aliyah self-image as an educated, highly-functional adult, I now had become someone who was essentially deaf, mute, illiterate, and culturally incompetent. When I walked onto the street, I felt as though people looked at me as mentally-challenged. Every time someone would say to me in a well-meaning way, “why don’t you try going to ulpan to learn Hebrew?,” I would cringe and my self-esteem would drop another notch.

I felt like I needed at least a temporary break from my struggles in Israel, so with considerable effort, I was able to convince my husband to spend the summer back in the U.S. In addition, this would give him the opportunity to earn an American salary for a few weeks. Since we had been subsisting solely on sal klita (monthly stipend from the Israeli government to new olim) while we studied in ulpan, the extra income was badly needed. My husband worked at a very high-paying job in rural America, and the children and I stayed with family members in the US.

Unfortunately, this trip presented a new set of emotional trials. I felt that I was rejected by my family. In the midst of a disagreement, they told me I could not continue staying at their house, and that I had basic personality flaws. As evidence, they cited the fact that my grandfather, who had lived with us before aliya, and whom I had helped look after for the last five years of his life, died angry with me. I reacted to this rebuke with feelings of guilt, loneliness, and a further plunge in my already teetering self-esteem. For the first time in my life, I envied people who did not have family obligations or religious compunctions and could take their own life.

Upon returning to Israel, my husband and I decided that we should move to a yishuv, a small rural village with selective admission, which we hoped would bring us a sense of community that we so desperately wanted. We began to explore our options with many of the religious yishuvim in the north and found a common theme. There was no housing to be found, unless you were willing and able to build a home—which we were not. The other message we perceived during our exploration was that the resident Israelis were happy with their status quo and were not looking for newcomers who were culturally different and Hebrew incompetent, (i.e., “we don’t want our nice Israeli community to turn into another Little America.”) After an extensive application process filled with less-than-enthusiastic reception, we finally found a rental on a yishuv that was willing to accept us.

During our year on the yishuv, I found that when I asked people for help, most of my neighbors were willing to give of their time and effort happily and generously. However, very rarely did anyone reach out to us, invite our children to their house to play, or have us for a shabbat or yom tov meal. It was hard to find others who shared our religious hashkafa. We were called “too Beis Yaakov” for the dati leumi (National Religious) crowd, but we knew that we could not fit in with the Israeli Haredi segment of society. Our children were also suffering. They were not accepted by the other kids on the yishuv who had mostly grown up with each other. They routinely heard from their peers, “We don’t want you here, go back to America.” They were also getting physically bullied, sometimes by children much older than them, and I could not speak enough Hebrew to intervene with the kids or their parents. I felt completely unempowered and felt a total lack of control over my life.

To make matters worse, I was physically isolated and felt stranded on the yishuv without the ability to drive. Although I was now in my mid thirties and had been driving in the U.S,. since age 17 and had never been in an accident, I could not pass my drivers examination in Israel. I also could not find a job without the necessary Hebrew skills and reliable means of transportation. I began to hate my life, cry a lot, have difficulty eating, and sink into major depression. My husband was frustrated with me. He felt that I was not giving Israel a fair chance and that my negative attitude was ruining our chance to have a successful aliyah.

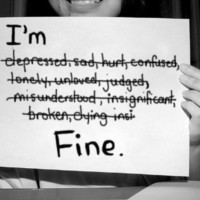

So, I felt like I had to keep everything inside. I was not comfortable to talk to my friends in the US about my problems, because when we spoke, they expressed awe at how fortunate had been to be able to make aliyah. I certainly did not feel like I could talk with our Israeli neighbors about my situation because I did not want to appear against their homeland. So I was living a lie, pretending to everyone to be happy in Israel, but in private, I longed to return to the U.S. every day.

Eventually, my husband realized that something was wrong with when he noticed that I had little appetite and was progressively losing weight. He found an American-Israeli CBT therapist that I could meet with on Skype. This became a bright spot in my life. She recommended that I find an English-speaking Torah learning partner, helped me find volunteer work in my field, and most importantly improved my poor self-confidence. I gradually got out of the dumps, and started to slowly make friends, develop realistic goals, and become more able to stand up for myself. She helped me communicate better with my husband and our marriage improved.

Then unfortunately, I relapsed. When I could not meet with her for one week due to internet malfunction, I completely panicked. I had had a difficult week and had expected she would be able to help me deal with my problems. When the help I was seeking that week did not materialize due to circumstances beyond my control, I panicked. It was then that I realized that I had become emotionally dependent on my therapist. Considering that I had never felt addicted to anything or anyone in my life, this dependency created a huge source of anxiety for me, especially knowing that our therapy was of a short-term nature.

I felt like I had failed therapy and went into a deep depression that even my therapist had difficulty helping me conquer. I became obsessed with death – wishing for it, davening for it, and wondering how I could accomplish it. I realize that for someone has never experienced depression, it is hard to understand how anyone can feel this way; but the emotional pain that I felt on a daily basis was worse than the most intense physical pain I had ever experienced (and I had gone through childbirth three times). Unlike regular sadness, where the sufferer expects that things will improve and that he can still determine his own destiny, I had a feeling of complete helplessness over my fate and hopelessness that the pain would ever go away. In my mind, my only way out was dying. I had never used alcohol or illegal drugs, but now I often wished I had access to these substances and I could take something – anything—to numb the awful pain.

Where was my emunah (faith) during this time? Before aliya, when I went through difficulties, I was comforted by my faith that Hashem controls the world and everything is bashert, meant to be. Depression is an insidious illness, warping the thoughts of its victims. I came to believe that the reason that I was suffering so deeply was that G-d was furious with me and, therefore, I must be a terrible person. I was burdened with the emotion of guilt, rather than feelings of bitachon (trust in G-d).

Through all of this pain, I confided in no one, completely embarrassed at how weak I was, ashamed about my bad feelings towards Israel, and worried that if my husband found out, our marriage would be permanently damaged. I had always been so careful to eat healthy, exercise daily, wear my seatbelt, and stay away from anything dangerous in order to maximize my chances of living a long, productive life. Now, I was preoccupied with death. My feelings intensified to the point where every time I’d pass by kitchen knives I would want to use them to harm myself, and every time I passed by our box of medicines, I would want to take enough of them to die.

I finally opened up to a couple of friends in the U.S., which helped, but it was not enough to get me to change my distorted thought patterns. I could not believe what was happening to me. I had gone from someone who disliked pain enough to never get her ears pierced to someone who was cutting herself with a knife on purpose, to reduce the emotional pain with which I was plagued with daily. Through all of this, the only thing keeping me going was the knowledge that I had a husband and three children who depended on me. If not for that constant thought, I am sure that I would have taken my life.

The following summer, our family bought us five airline tickets to the US so we could visit them. After my last summer in the US, I was very nervous about the upcoming trip and was having great difficulty sleeping. I discussed this with my family doctor. She diagnosed me with depression, and prescribed sleeping pills and an anti-depressant. I took the sleeping medication as needed, but I could not bring myself to take the anti-depressant; that would require that I admit that I had psychiatric illness, a fact that I was not ready to face.

The summer trip was an emotionally tumultuous experience, which further worsened my depression. One night in the US, while staying with relatives, I remember forcing myself to go to sleep on my hands so that I would not be able to take the entire box of sleeping pills next to my bed. On the one hand, I had a strong desire to fall asleep and never wake up, but at the same time I knew that my husband and children were counting on seeing me alive the next morning.

By the time we returned to Israel, which I had begun to see as my prison, I wished so much to die that I basically stopped eating, and I was so troubled by the conflict in my mind over whether or not to commit suicide, that I could not sleep at night. After a few days of almost no food or sleep, I knew I was in trouble. I could barely muster the strength to make my daughter a tuna sandwich for dinner. I knew that I could not go on like this, so I finally opened up to my husband. He seemed to take the news better than I expected he would.

He promptly took me to the local hospital ER for an immediate psychiatric assessment. I was given three prescriptions, told to continue therapy, and sent on my way. One medication gave me such bad tremors I could not continue it, but the other two had side-effects I could live with. The medications did help reduce my anxiety and dampened my suicidal impulses. At this point, we had started settling into our new community to which we had moved just prior to our U.S. trip.

Thank G-d our new home was a much more suitable place for us. I told people in the neighborhood that I was “sick,” and they really became a source of support for me. It was warmly reminiscent of our old community that we had left in the U.S. I opened up to a few more friends in the U.S. and Israel and was pleasantly surprised to see that these confidants continued to respect me and like me, despite my failings and weaknesses. I was no longer the “perfect” spouse, mother, and friend, but I still had a devoted husband and friends who stuck by me.

With supportive people in my life to confide in, I did not feel so dependent on my therapist. Some of my friends and my husband began to daven and say tehillim for me regularly, and my husband donated money to a yeshiva that prayed for me daily at the Kotel. My husband further offered to take our family back to America irrespective of all financial consequences (i.e., we would owe NBN the grant back) if it was necessary for my mental health. Also, the fact that I did not have to hide so many things from my him reduced my anxiety level. I was starting the road to recovery.

The next few weeks were spent in fear – my husband forbid me to go to a gorge near our house because he was afraid I would jump off, medications (except the antidepressants I was taking) were stored at a neighbor’s house, and all sharp implements were hidden away. If I had a headache, I was out of luck, and if I needed to tighten a screw, cut vegetables, or remove a loose thread from my clothes, I had to wait for my husband to get home from work to bring out the tools from hiding, and then replace them. During this time, I was able to convince my therapist to increase me temporarily to twice a week. I also started meeting weekly with a life coach and with a social work student. Thank G-d with all of this support, I improved tremendously to the point where I began to once again love myself and my life and even enjoy being in Israel.

Now looking back on this experience, I wonder why this happened to me, what I can learn, and how I grow can from it. First, my attitude towards mental health has changed. I used to think that people who had mental/ emotional illnesses such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders, alcoholism and other addictions either had a “problematic” genetic history or had gone through abusive or traumatic childhoods. I never thought something like this could happen to me. I think I have become a better listener and more empathetic to people who are suffering.

I also realized that a person’s subjective state of mind is so much more important than their objective reality. If someone is battling physical illness but has a positive attitude about his life, that person is in a much better position than someone who is may appear to have an almost perfect life, but suffers from depression. I also used to be very much against use of antidepressants, thinking that people should address the root of their problems, rather than try to medicate them away. Now I realize that depression is largely a biochemically-based disease and, just as some diabetics need insulin to regulate their blood sugar, depression is a state of serotonin deficiency and may require pharmacological intervention.

I also have learned that I do not need to be perfect, and it is okay if, once in a while, my children watch a movie because I feel too exhausted to parent them or if we have plain pasta or take-out pizza for dinner every now and then because I do not have the stamina to cook anything more nutritious. I think I have also learned how to be able to be assertive in a country where aggression is more of the norm and how to make myself heard. I am still working on not giving weight to what other people think of me. For example, I know that I took good care of my grandfather and that we had a loving relationship even if my extended family thinks otherwise. I know that I excelled academically, even though when people hear me speak Hebrew it may appear otherwise.

I now see that the fact that I battled depression and still managed to be a pretty good wife and mother even on days where just getting out of bed and brushing my teeth in the morning felt like a Herculean effort means that I am not weak as I once thought. Rather, Hashem imbued me with inner strength even in the worst of times. My parenting style has also responded to the lessons I’ve learned from therapy – I no longer try to shield my children from all of the normal hardships of growing up. I do not want them to have false sense of comfort in life. Instead, I appreciate that the challenges they face now can be used to bolster their resilience and reduce the likelihood that they will one day fall into to the grasp of depression.

I hope that as someone who has suffered from clinical depression, anxiety, and suicidal thinking that I will one day be able to help other people in that situation. Most of all, I now realize how fortunate we are if we wake up with vitality; how wonderful it is to look at our children and say to ourselves, “I hope to be alive to see them grow up, get married, and have their own children;” how magnificent it is to enjoy normally pleasurable experiences such as eating, spending time with loved ones, engaging in a hobby, or relaxing with a favorite novel or movie.

I used to pray that I should have a long, healthy life, shalom bayis (marital harmony), enough money for my family’s needs, and the ability to raise successful, Torah-observant, healthy children. Now I mainly daven that I should feel strong enough to be able to cope with life, regardless of what tests G-d brings my way. This is truly being alive.

************************************

Last week I woke up thinking about what an ideal wish would be – I shared that with you in my post last week . That morning I spent quite a bit of time thinking about it but I was focused on what wish would give me the concrete results in my life I wanted – health, prosperity, etc. Then later the same day I received this letter. In her closing words, she hones in on what the ideal is – to be strong enough to cope with whatever comes our way.

Avivah